Here comes a regular

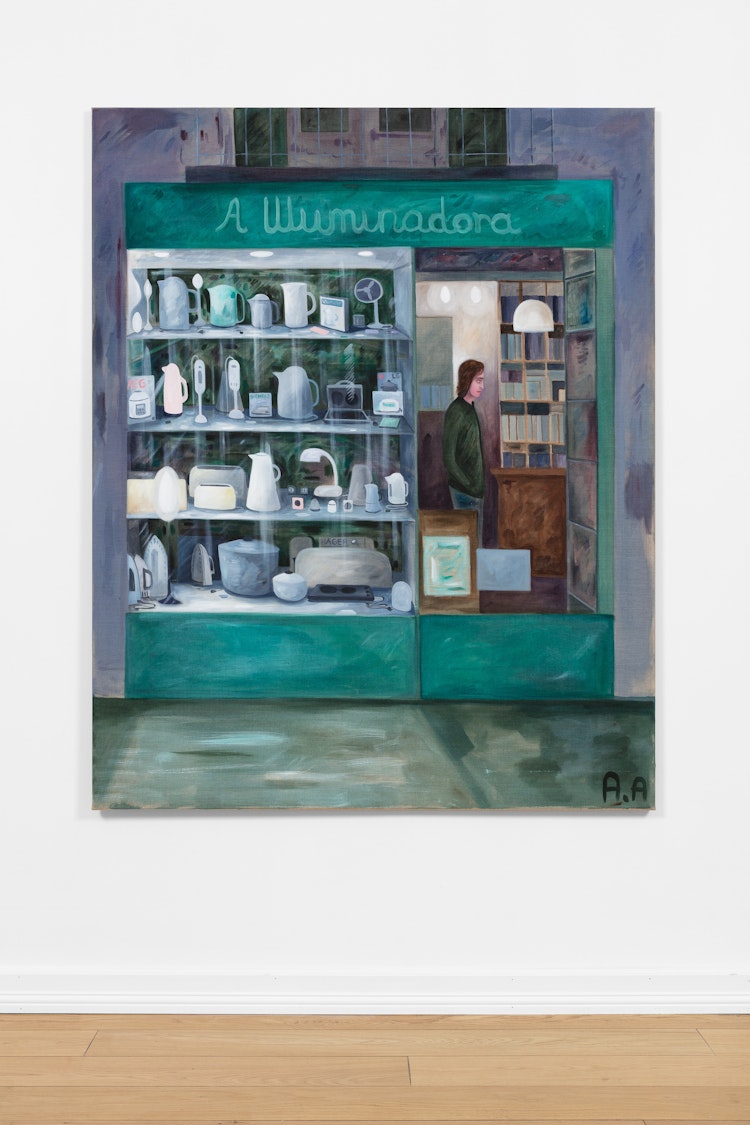

Like peep-holes through a paling fence, Audun Alvestad’s new series of paintings invite into a glimpse of the everyday life in his neighborhood. What matters is not which neighborhood it is, even though the general fauna and the language pictured are tell-tales of Lisbon, instead, the focus is on the more general social life in his immediate surroundings.

Moving away from the more intimate rooms and actions in his earlier paintings, where the spectator was invited to more or less actively participate, he is now focused on a different social action. The position is now to that of a bystander, with decisively more distance and also as someone more passive in their position. The color scheme is different as well, it can be described as more dramatic, and the palette is darker.

The frontal perspective of the paintings leaves us with a very flat view of the small spaces portrayed, and the perspective and depth is created through the windows in the pane. What we experience is not about the individual and identifiable specific spaces that the paintings represent, but instead a more general sense of street life. This very type of street life was more common within the Northern Hemisphere 40-50 years ago before the mallification of our more and more globalized cities started. The continental streetlife is however still widely existing and functioning in the south of Europe, even though tendencies towards the same direction of the north are clear.

Change is of course inevitable over time, and lock-down sure took its extra toll on the type of smaller local stores connected with a lively pedestrian cityscape, and the social life of many. Instead of going to your local cheese supplier, butcher, vegetable shop, etc where the keepers know your name, where you live, and what your preferred type of slicing is, there are now the global home delivery options of Gorillas, Volt, Foodora, or other Amazon-like monsters, offering a wider variety and virus-safe, effortless online shopping.

Or, that is at least until we recognize what this changed type of consumerism actually mean for the most often deeply exploited, precarious carrier workers of course, or until we have to become a delivery worker ourselves in order to survive on minimal wages. By then, this type of shopping becomes deeply unattractive, especially when the consequences of it mean the end of the picturesque restaurant on the corner or the close-by tobacco shop owner who used to give away samples of candy to cute kids.

Certainly, no one seeks out to identify as a Luddite, but as the easing of lock-downs are on the horizon, it's essential to start imagining not only what changes in our lives are necessary but also what changes are desirable. It is easy to look at the type of streetlife portrayed by Alvestad in a slightly nostalgic and romantic light, but maybe that’s too easy? Maybe other options are more sustainable and still may offer the so important daily social aspect, especially for those who live alone. Alvestad offers no answers with his contemplative tableaus concerning the functions so essential for our habitat in the urban area. But he certainly triggers questions about what we really need to feel comfortable and satisfied, and how we may obtain it without causing environmental or exploitative harm?

The peep-holes Alvestad is offering us, are indeed just as reflexive as the window-panes in the very same paintings. They offer us a surface that catches us within our every day, socially distanced, path of capitalist realism. So, where do we go from here?

Hva leter du etter?