Artificial Intelligence

Dukkehodet har vært en gjenganger i Marianne Heskes kunstnerskap helt siden 1971, da hun snublet over en eske fylt til randen av dem på et loppemarked i hennes daværende hjemby, Paris. Det standardiserte og anonymt utseende dukkehodet i pappmasjé måler ikke mer enn ti centimeter, og har antageligvis blitt brukt som leke på 1920-tallet. Men det er ikke dukkens funksjon som barneleke som interesserer Heske, ei heller de fetisjistiske eller rituelle aspektene ved dukken som opptok blant annet surrealistene noen tiår tidligere. I Heskes kunstneriske virke representerer dukkehodet selve mennesket, og hun iscenesetter det for å belyse tematikker knyttet til identitet og mellommenneskelige relasjoner. Et sitat fra Shakespeare-stykket As You Like It dukker ofte opp i Heskes notater relatert til dukkehodet: «All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players». Ved å løfte frem denne gjengivelsen peker Heske på det nære forholdet mellom det sosiale og det teatrale, hvordan vi alle spiller en eller flere roller i våre egne liv. Det at dukkehodet ofte presenteres som en maske eller marionettlignende figur i verkene hennes, understreker nettopp denne koblingen.

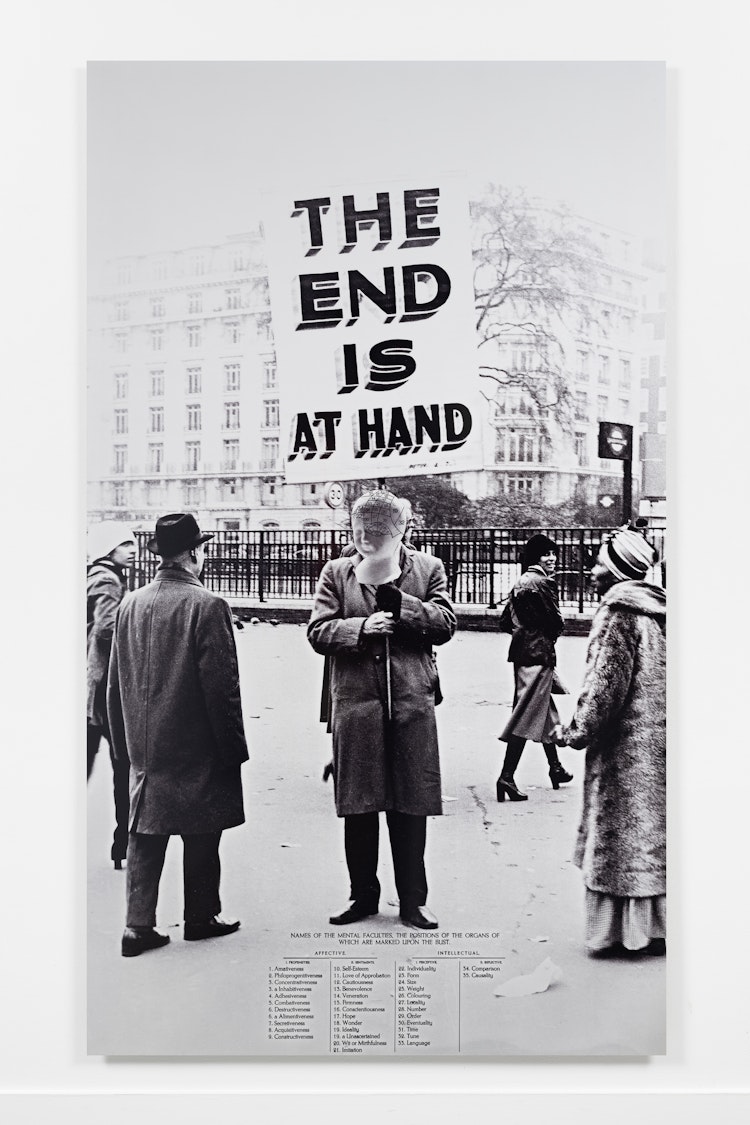

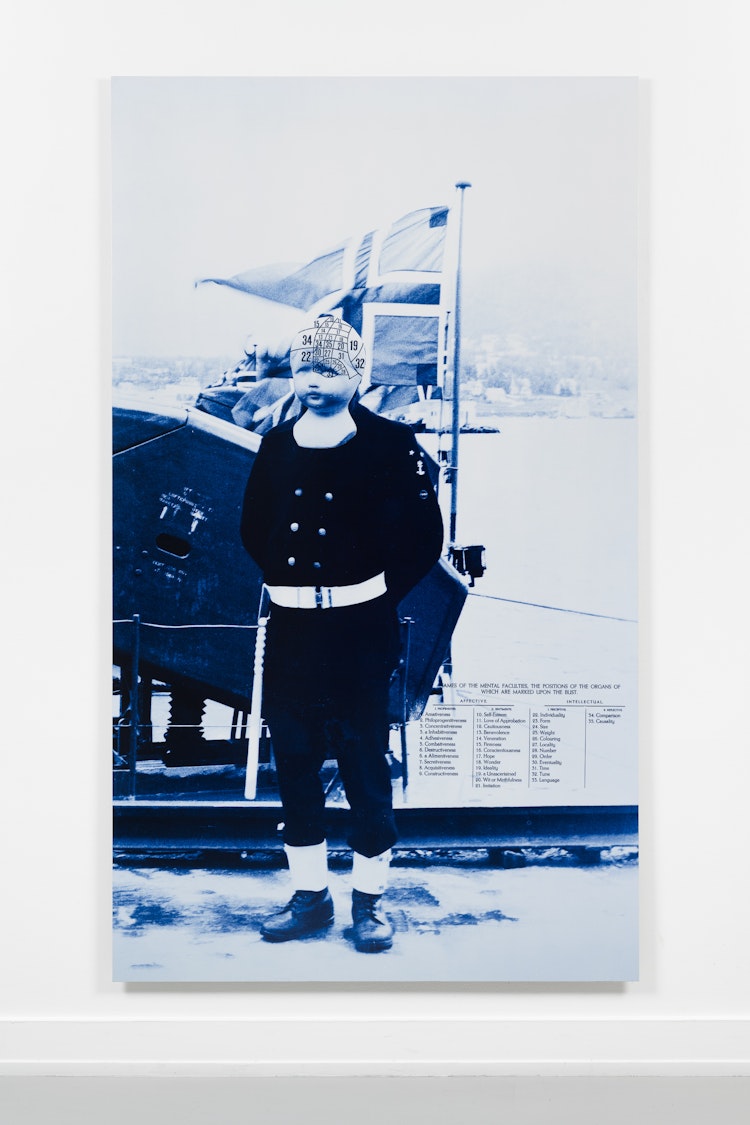

Gjennom 1970-årene, som Heske tilbringer som student i det kontinentale Europa, er dukkehodet fellesnevneren i verk som ellers varierer kraftig i form: Vi finner dukkehodet som statue, i video- og fotoverk, i grafikk, kollasjer og performancer. Tematikken varierer også. Verkene realisert i Heskes parisiske periode (1971-1975) er for eksempel interessante å betrakte i et feministisk perspektiv. Flere av dem stiller spørsmål ved sin samtids kvinnerolle, både gjennom formspråk og mer eksplisitt gjennom titler som Sois belle et tais-toi (vær vakker og ti stille). Videre, som student ved Film and Television-linja på Royal College of London (1975- 76) eksperimenterer Heske med nye teknikker, og vi finner blant annet dukkehodet mangedoblet til det som minner om voldsomme folkehav, eller som en hvit maske over apatiske TV-titteres ansikter. Disse presentasjonene av dukkehodet oppmuntrer til refleksjon rundt interrelasjonelle problematikker på et politisk nivå, som individualitet i massemedienes tidsalder og i møte med strømlinjeformede storbyliv.

Det er i denne logikken serien Phrenology Photo Analysis skriver seg inn. Blåst opp til to meters høyde er de avfotograferte kvinnene og mennene på størrelse med oss selv, men dukkehodene som maskerer ansiktene deres umuliggjør øyekontakt. Noen er ikledt uniform, andre tradisjonelle kostymer eller hverdagsklær som reflekterer deres plass i samfunnet og geografiske tilhørighet, som går fra Karasjok til Marrakech. Til tross for den store variasjonen blant modellene påtvinger dukkehodene dem et uniformt preg, noe som blir ytterlig understreket av den påtegnede, nummererte oppdelingen av dukkenes kranier. De viser til et skjema med påskriften «Names of the mental facutlies, the position of the organs of which are marked upon the bust». Skjemaet er inndelt i kategoriene «Affective» og «Intellectual», og inneholder en liste over 35 personlighetstrekk som svarer til de nummererte partiene på dukkehodene.

Heske refererer her til den pseudovitenskapelige læren om frenologi, en teori som ble utarbeidet av 1800-talls-legen og fysiologen Franz Joseph Gall. Tanken var at våre personlighetstrekk kommer til syne i hjernens fysiske struktur og videre på hodeskallens ytre form. Inndelingen i 35 partier skulle gjøre det mulig å avdekke et menneskes personlighet ved å kjenne på skallens fasong. Til tross for at dette positivistiske ønsket om klassifisering ble vel mottatt i sin tid, er teorien en del av strømninger som etter hvert kulminerte i eugenikk, biologisk rasisme og etnisk rensning. Denne mørke historien er Heske fullt klar over. Hennes eksplisitte referanser til frenologien kan tolkes som en kritikk på enkeltmennesket så vel som samfunnets ønske om klassifisering og standardisering, et ønske om å konformere som forenkler og går på bekostning av vår individualitet i møte med andre. Problematikken er fortsatt aktuell, og er kjent fra flere av Heskes nyere verk, som det gigantiske Hodet N.N. (2014) plassert i Torshovdalen.

Sosial kritikk har alltid vært en viktig del av Heskes kunstnerskap. I sin publiserte notatbok fra 1970-tallet skriver hun om bruken av dukkehodet i sin kunst at «jeg prøver å påvise det absurde i vår situasjon i dagens samfunn og bidra til bevisstgjøring om vår manipulerte (marionette)tilværelse, om hvor lite vi egentlig bestemmer over våre egne liv, våre egne holdninger og oppfatninger». Denne tankerekken er et eksempel på en tematikk som fortsatt står sentralt i Heskes kunstneriske virke, og det er i denne sammenheng utstillingens tittel, Artificial Intelligence, skriver seg inn. Mange av 1970-talls-verkene til Heske, deriblant Phrenology Photo Analysis, kan lede tankene hen til den kraftige robotiseringen av dagens samfunn. Hva gjør denne fremveksten av automatisering og kunstig intelligens med vår evne til å tenke selvstendig? Heske lar spørsmålet stå åpent.

- Ingrid Holden

- -

We are all haunted by an algorithm.

Artificial intelligence systems are capable of teaching themselves, and like artists that works with concepts, able to process and organize a large amount of data. The difference in processing, however, is the one between knowledge and intelligence. Marianne Heske has decided to revisit some files from her past through a confrontation with Artificial Intelligence. The artist presents a new cycle of works that is a sophisticated update of a portion of her large personal archive, which she reactivates in a successful series of artworks linked to her beginnings.

In the 1970s, the artist became interested in a pseudo- science that attracted her attention, giving rise to a complex activity of investigation. The interest in phrenology was just a visual aid to analyze behaviors and attitude of a mass society in search of tools to classify the human soul. Her research followed a protocol and the nameless people she pictured in the different places she lived and visited are like a multitude of individual, anonymous dolls. London, Paris, Amsterdam, Oslo, Tromso, Karaskjok or Marrakesh, the work became a conceptual map. The same head with circles and numbers and a precise position for emotions and attitudes in our brains, repeated, precisely because she was aware of the contents of what had turned out to be a huge scientific bluff. She had conducted her work, through the new media (video and photography), very popular at the time, and with the evident intent to oppose the phenomena of standardization and homologation, manifested early in Western society and lately swept the planet. An ante litteram vision of what would have happened in the new digital age, in which digital commodity has entered our everyday life, generating pleasure and addiction.

When we think of Artificial Intelligence, we imagine the development of learning algorithms. We are surrounded by spam, filters and daily applications. Artificial intelligence, in conjunction with Big Data procedures, is an effective integrated technology - not at all visible but always active 'in the background' of our portable “smart” phone. It is a camouflage of technology that produces a problem, behind the screen we use every day, a network of actions rhizomatically unfolds. Screen users no longer see and no longer even control. When we compare our brand-new tools to the studies about the brain made few centuries ago, after a first smile, we cannot fail to notice something strange. Probably the roots of the many formats of our digital era lay in those false phrenological ruminations about the shape of human skull or in these old physiognomy studies. Even a false science was capable of providing mapping of needs that fulfilled feelings, emotions, attitude. Summarized in today’s media, we can recognize icons of contemporary life like the e-moijs in use and with which we close, gloss and punctuate the new order of our speech, all along our communication. Can we interpret them as direct derivatives of the many nameless heads of Marianne Heske's dolls. The artist can successfully reclaim the wonderful protocols of her own conceptual past. Then these photographs of her will appear almost prophetic in the reshaping an old format. Accompanied by videos and performances, they make clear the power of strength in the sophistication of the image.

In the texts associated with the artist's work, back in the seventies there was a lot of emphasis on the idea of masks. It is evident in the new picture’s enlargements (color and black/white), in their analogue manipulation, that they are nothing but the germinal form of all the digital practices used by the artist in the past years. Marianne Heske produce an alchemical mix of analogical and digital as a constitutive element of cultural and relationship practice. Digitization contributes exceptionally to the transformation of life itself into a data structure. Everything can be embodied and visualized - with the help of interfaces. Now, however, the doll, the puppet and the collage are no longer used to create masks but to embody contemporary avatars. Their symbolic function is now adapted to another era.

When we attempt a parallel with the simplification introduced by algorithmic calculation, the idea of reducing information relating to human typology and anonymity is provocative and revolutionary in itself. If summed up in a head that bears inscribed and make visible signs of the cerebral localization, of our feelings and our abilities, became among all that an interpretation of the world. Marianne Heske’s infinite heads are also showing that our civilization is proceeding inexorably. We developed the 'computer in us' long before the computer existed as a physical machine. Originally, algorithms were simply rules applied by humans, to make thought processes transparent and definable. The difference between consciousness and intelligence is all here seems to suggest Marianne Heske with her artistic practice constantly tinged with surrealist’s humor. All conviction is an illness to tell it with Francis Picabia. The hypothesis that the artist exists precisely to propose, in spite of science, the most correct hypothesis to support the transformation of the cosmos into information and possibilities of succeeding are not so remote.

- Ivo Bonacorsi

Marianne Heske, 15 Phrenology Photo Analysis, 1977-78, aluminum charts indicating 35 human faculties, 215 x 125 cm

What are you looking for?